“Ni de aqui, ni de alla” How Frida Kahlo embodied the 21st-century 2nd-generation immigrant narrative.

“Ni de aqui, ni de alla”

How Frida Kahlo embodied the 21st-century 2nd-generation immigrant narrative.Following the recent and continual wave of mass-immigration fueled by the American Dream, the generation following such have asked themselves: “Who am I?” Growing up for any 2nd-generation immigrant in the United States brings several 21st-century challenges, most notably in the sense of identity. The phrase “Ni de aqui, ni de alla” (Neither from here, nor from there) has grown prominence as a way to verbalize the feeling of not belonging to either the United States or their family’s country of origin. This feeling can stem from many aspects, including but not limited to a language barrier, a lack of cultural understanding, or a conflict between cultural values and modern aspirations. For many Mexican-Americans of this group, there exists one figure who embellishes this sense of place: Frida Kahlo.

Born in 1907, Frida Kahlo was not destined to become the face of Mexico and Latinx identity as she is now. Daughter of a German father and a Mexican mother, Frida embodied two mixed identities forced into the frame of Mexican. Suffering from both polio and a tragic traffic incident as a teenager, Frida would struggle with physical disabilities and the mental after-effects of such horrible events for the rest of her development. Yet, Kahlo preserved; using the resources available to her to express herself through the medium of art.

As the mother of modern dual-identity, Kahlo consistently pushed for expression and appreciation of traditional culture, specifically through the Mexicayotl movement. Through it, she idealized Mexico for its rich ancestral and indigenous art and culture during a pivotal age of political instability of the Mexican revolution, post-colonialism, and the reconstruction years after. As a modern woman and thinker, Kahlo consistently tackled the personal question, “Who am I?”

In this essay, we will be examining two monumental pieces in that Kahlo expressed these ideas, which still remain as impactful as they were decades prior.

Las Dos Fridas

“Las Dos Fridas” c. 1939, oil on canvas

|

On the right, a more relaxed Frida renders herself as a more traditional representation of a Mexican woman, wearing a traditional Tehuana dress. A Tehuana dress typically frames women as a glorious secluded beauty, rooting from the matriarchal society located in Tehuantepec, Oaxaca. This is the identity that her recently-divorced lover, Diego Rivera, loved her as.

|

Both of the Fridas’ have their hearts visible to the viewer, connected to each other through the main artery. On the left, her heart is sliced open, possibly hinting at the emotional breaking of her heart by Diego, with a vein running down her arm, sliced by pincers and staining her white dress. The continual drippage of blood shows Frida as bleeding to death, possibly representing how the culture of her Mexican mother in her bloodline socially “stains” the expected European or modern class that she internally feels uncomfortable as.

|

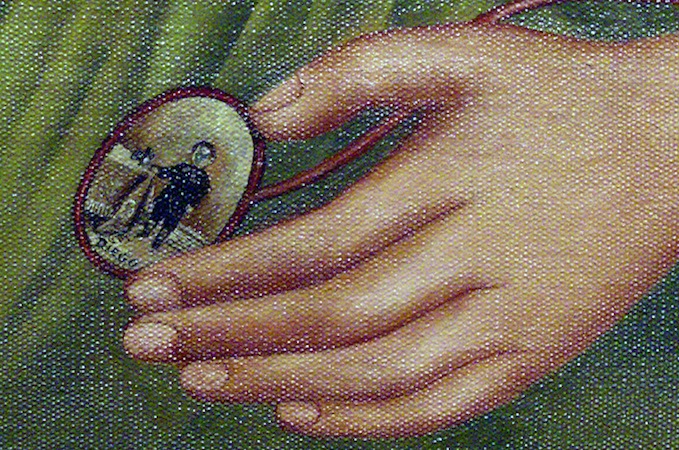

| Portrait of Diego held by right Frida |

On the right, Frida is holding a small portrait of Rivera with her blood and veins remaining intact. This discrepancy between her blood, posture, and ensemble shows the artists’ dual-identity. Yet, both halves remain distinct and contradictory to each other. On one hand, the representation of the white beauty on the left shows a “modern woman” that Frida was trying to be, yet shows the internal turmoil of her culture setting her back. On the other hand, the traditional Mexican rendering of Frida shows her contempt and relaxed, yet still with Diego and possibly even suppressed by Mexican standards of women. Both renditions of Frida are seated holding hands, maybe showing that there is a possibility of finding a happy medium through a sense of resiliency, yet both looking past each other without recognition as their own determined, confident and developed persona respectively.

Therefore, it is unclear to the viewer and to historians which side Frida prefers, or wants to become. Regardless, “Las Dos Fridas” represent the struggles that speak to the 2nd-generation immigrant conflict between the familiarity behind culture, tradition, modern expectations, modern ambitions, and the subconscious, while putting in question the validation or personal-fulfillment of modern living.

Self Portrait Along the Border Line Between Mexico and the United States

| Self Portrait Along the Border Line Between Mexico and the United States c. 1932, oil on canvas |

On the right, gloomy industrialized United States is shown with smokestacks blocking the sun, skyscrapers, modern inventions, and capitalist entrepreneurship shown with the inclusion of “Ford” spelled on the smoke towers of a factory. Underneath, metal ducts are lined almost as marching figures, with machinery and wires replacing plant life and roots.

|

| Detail showing plants and figures |

In between two worlds, Kahlo stands defiantly. Asserting herself as a mixture and product of both the modern and ancient world. As a modern woman, Kahlo remains distinct in a world where innovation leaves culture behind. Almost as if she is saying “I’m still here!” Kahlo holds a Mexican flag in her hand as she enters the modern world as a modern woman, yet still remains true to her background.

During these trips to the United States, Kahlo often wrote in her diary of her distaste for modern living and yearned to return back to her Mexico. Yet, as a modern woman, Kahlo also has to recognize that her limelight in the globalized world also brought into question her truthfulness to the Mexican culture. This painting evokes the idea of missing the idea of home, but does home miss you?

Frida Today

Labeled as a surrealist by the Western art world, Frida hated commercialism and any labels. Frida’s face can be found mass-produced everywhere as a symbol of Mexican nationalism: on the 500 peso bill, souvenirs, tourism memorabilia, and as Salma Hayek’s notable performance in 2002’s melodramatic motion picture Frida.

To the modern world, Frida is seen as a symbol of Mexico, Latinx culture, feminism, surrealism, and more. But to many, shes more. She’s seen as a mother, as a mirror, and as a window to the familiar and to the unfamiliar.

Comments

Post a Comment